For the more than one million Americans who've passed up the life of urban sprawl in favor of traveling the country in their recreational vehicles, this is no fantasy, it's everyday life.

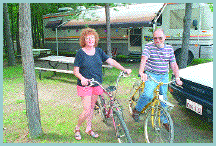

"Home is where you park it," a philosophical Jim Kimmins says of his RV-cum-residence. "We planned this out for eight years, and I think this is even better than we thought it would be," says his wife, Maralyn. The Kimminses, who've been on the road for about a year, used to park themselves in a far more traditional house in Canton.

They're part of a national boom in RV users. Sales of RVs, which for statistical purposes also include towable units such as campers and travel trailers, are expected to soar through the '90s as baby boomers enter the prime RV-buying years, age 45 to 54, according to the Recreation Vehicle Industry Association. According to a recent University of Michigan study, 44 percent of RV owners are 55 and older, while 39 percent are between the ages of 35 and 54.

The concept of living full time on the road is simple: Although far smaller than the average permanent home (the Kimminses' quarters encompass all of 300 square feet), today's motor homes provide comfortable, modern accommodations for their dwellers. RVers have refrigerators, computers, stereo equipment, microwaves and satellite dish-enhanced TVs at their disposal.

What they don't have, though, is what many people don't want anyway: Stress.

"I traveled for Chrysler for 30 years, going from airports to rental cars to hotels," says Jim Kimmins. "There's no Maalox or Tums in this lifestyle. The stress is gone."

Kimmins pauses. "Of course, if you don't like to tow or drive a motor home, then it's stressful - but you won't pick this lifestyle, either. If you want to sit at home and spend your retirement being a couch potato, this is not the lifestyle for you."

Rather, the life of a full-time RVer is nomadic, spent roaming from one campground to another with mostly the basic necessities. It is a chance to get back in touch with rustic America, something foreign to many urbanites.

"We take the back country roads, visit the small, little towns and meet people we've never had the opportunity to meet," Maralyn Kimmins says. "Having lived in the big city for so many years, you find there are things that happen there that don't happen in the smaller towns. Doing this really helps you regain faith in humankind and regain an appreciation for this nation that perhaps a person loses when living every day in corporate life."

This includes going to a local high school football game, participating in potluck dinners, going to band concerts and really becoming immersed in a community for weeks at a time.

RVers also disprove the adage that you can't take it with you. "The big advantage of this lifestyle is that you get to travel and see a lot, but you're also living at home," says Ron Hofmeister, who with his wife, Barb, has co-authored a book about full-time RV living called An Alternative Lifestyle: Living and Traveling Full Time in a Recreational Vehicle, and an RV-lifestyle newsletter, Movin' On. "If you have a house and wanted to do all this travel, it would be (cost) prohibitive."

"We don't have to worry about smoky motel rooms or sleeping in beds other people have slept in," says Barb Hofmeister. "Our home is always with us."

Along with the back-to-nature mentality that many full-timers share is another love: the lower cost of living. Ron Hofmeister, a former deputy finance director of the Michigan Department of Transportation, is considered an expert on budgeting for the lifestyle - and with more than seven years on the road, he has the credentials. He says full-timers pay up to 40 percent less in household expenses than people living at permanent addresses.

Depending on whether you buy new or used, and, of course the size of the vehicle, an RV suitable for full-time living ranges from around $40,000 all the way to $1 million for those bus-size behemoths used by rock stars. The Hofmeisters started out with a $30,000 vehicle and eventually upgraded to a larger, better-appointed model.

Rent, utilities, property taxes, maintenance costs and other fees associated with home ownership do not exist in the world of full-time RV residents. The Hofmeisters' monthly budget of $1,615 has only four major expenses besides their monthly RV payment: $350 for groceries, $300 for recreation or dining out, and $175 each for campground fees and fuel. The fuel is for both their RV and their accompanying Toyota pickup truck, which they use for excursions into town, as it's rather cumbersome to unhook an RV from its site just to go grocery shopping.

Hofmeister says even their budget can be chopped. "There are countless ways to lower campground costs, and $175 merely represents our experience based on a combination of membership parks, commercial campgrounds and public parks," he says.

Some parks reserve sites only for members, such as Smoke Rise, located east of Flint in Genesee County's Richfield Township. Smoke Rise, where the Hofmeisters and the Kimminses recently stayed, is a Coast To Coast campsite, meaning only members of that organization can stay there. Maralyn Kimmins says that by buying a membership prior to retirement and becoming full-timers, their campground costs are covered by $4-per-night vouchers.

The Hofmeisters get more mileage out of their campground budget by either "boondocking" (camping in roadside rest areas, parking lots and other safe and legal places to park) or by volunteering time at public parks.

A common type of public volunteering is called "campground hosting." A campground host is comparable to that of a park ranger proxy, assisting other campers with park information, rule interpretations, campsite selection and even emergencies requiring outside assistance.

Full-timers also pitch in when disaster strikes. When torrential rains flooded the Mississippi River a few years ago, many full-time RV dwellers revised their travel plans and headed to Iowa and Missouri to assist the cleanup effort.

Despite all the positives full-timers experience, they admit there are a few drawbacks. Minor expenses include mail forwarding and voice mail services - essential for full-timers because they don't have a permanent address and rarely hook a phone line into the RV.

"You'd better get used to the world of pay phones. Cellulars are nice - they're OK for emergencies - but they're not cost-efficient for everyday use," Ron Hofmeister says. "Any full-timer will tell you that not having a regular phone is the biggest drawback to this lifestyle."

"We have provisions to hook up a phone line, but the only time we use it is when we know we will be in one place for two or three months," Jim Kimmins says. "We call for messages daily and get first-class priority mail drops once a month."

Adds Maralyn Kimmins: "Because we don't have a phone, I can't access the Internet, which is something I'd really like to do. I feel in a way that I'm missing out on it."

Along with missing direct phone calls from children and friends, some full-timers miss having a permanent church or school system. (You don't have to be a retiree to partake of full-time RV living; younger people have been known to home-school their children.) They also sometimes have difficulty explaining the rationality of selling or giving away their worldly possessions in favor of life on the road.

"We trained our kids in terms of what we're doing," Barb Hofmeister says. "We told them, 'We're not jumping ship and we're not abandoning you. We want to keep in touch and we want you to call, and we will call back. And we will visit you, because our house has wheels."

"Much of our old furniture is divided up among our kids, and whenever we see them there's always a reminder of our former home there," says Jim Kimmins. "Most of our kids handled it pretty well, although we were asked a lot of times by one of our sons, 'Are you done yet?'"

"We know people very close to us who think - and have voiced to us - that what we are doing is absolutely crazy: 'You're so radical! How can you sell your house?'" he adds. "Let me tell you, I've had enough of shoveling snow! I've had enough of gardening! I've had enough of paying property taxes and association fees and getting nothing for it; to heck with that!"

This article originally appeared in The Detroit News.